The Importance of Being Lost

- Ana

- Oct 5, 2024

- 7 min read

A story of an incredible resilience, PTSD, attachment, and post-traumatic growth. And how sometimes one needs to be truly lost to find one's true self.

I don’t play favorites with my clients. I really don’t. But if I did, Bobby would be one of them and one of the reasons why my job is the best job in the world. This is Bobby’s story.

On Getting Lost

It happened 20 years ago.

A young man was stabbed, and Bobby, helpless, could do nothing but stand there and watch the young man bleed to death in front of him. Afterward, covered in blood, Bobby walked the cobbled streets of this foreign town back to his hotel. To this day, he still remembers the sound his shoes made as the coagulating blood stuck to the cobblestones beneath his feet.

Back to his hotel room, Bobby didn't wake his friends, who were fast asleep. He was afraid that they were going to make fun of him, think of him as a softy, weak. And what would be the point? The deed was done. He just had to "get on with it," as they say in the North West of England.

The next day, he called his mum back in England and said, “There’s been a murder. I’m fine.” And that was that. For the next 18 years, that was all he ever said to anyone about what had happened that night in that foreign town.

But inside Bobby, stormy clouds were gathering, and a different story was beginning to unfold.

One life was lost that night, and another - Bobby’s - was about to be lost in a different way. He began a slow but certain descent into a downward spiral of psychological, emotional, and ultimately physiological consequences of the trauma. Bobby’s torment remained completely silent and inward, without anyone knowing.

PTSD

Bobby would spend the next 18 years in the grips of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) that slowly but surely took a hold of his habits, identity, and life itself.

Every night for the next 18 years, he experienced the same nightmare, its sinister storyline unfolding in a meticulously identical manner, replaying the murder even in moments when the brain was supposed to rest and regain strength for the day ahead. He would wake up in the middle of the night, unable and unwilling to go back to sleep, leading to chronic and severe sleep deprivation that persisted for many years.

That felt like a hell on Earth, but there was more to come.

Always on edge, Bobby avoided large groups of people, compulsively checking what others held in their hands, wondering if they might be about to strike. It had happened once, so it could happen again, right?

And then he slowly withdrew from new experiences, from new encounters.

At that point, he still didn’t say anything to anyone. He was resolved to get through it on his own. What was the point in mollycoddling himself, and he didn’t want anyone’s pity. What could others do, anyway?

But things were not getting better, they were getting worse. The panic attacks started. They were becoming more and more frequent. Bobby at this point could not sleep or function anymore. His mind and body were breaking down. He had to look for help.

A Non-Believer

In our first session, Bobby didn’t mince his words. I still remember how he looked me in the eye and said something to the effect of, “I’ll be honest with you; I don’t really believe in THIS” - as to say sitting here and having a chat is not doing anything, is it?

Bobby was a non-believer.

What I could not tell Bobby then, but what he was about to discover on his own, is that while the nature of therapy is transactional, the connection is real. That even just sitting and talking is, in fact, much more than just that. And that therapy is many things and certainly more than merely sitting and talking.

But it was too early for that. We were just beginning the long and winding journey back. I needed tangible proof that therapy could make a difference for Bobby, and I needed it fast.

And then, bingo - I found the solution. Some time ago, I had acquired a galvanic skin response measuring device that provides a measure of physiological stress. I used it to demonstrate to Bobby how we could intentionally regulate and reduce stress through techniques learned in therapy. Below is the original reading that convinced Bobby to get on board and bought me time to allow other effects of therapy to take place.

Doing The Work - The Long Journey Back

The rest is more or less history now. We did the work. Diligently. For months. Maybe even years.

First the hyperarousal. Check.

Then the intrusive thoughts. Check.

The hypervigilance. Check.

The avoidance. Almost check.

And then the nightmares. We dealt with that so well. Bobby is nightmare-free now. We were both so pleased with that work.

Nightmares. Check.

But as we peeled back layer after layer, one thing remained at the centre of it all. The last stronghold of our work. Bobby's attachment.

Given Sufficient Pressure, No Man Is An Island - An Avoidant Attachment Cautionary Tale

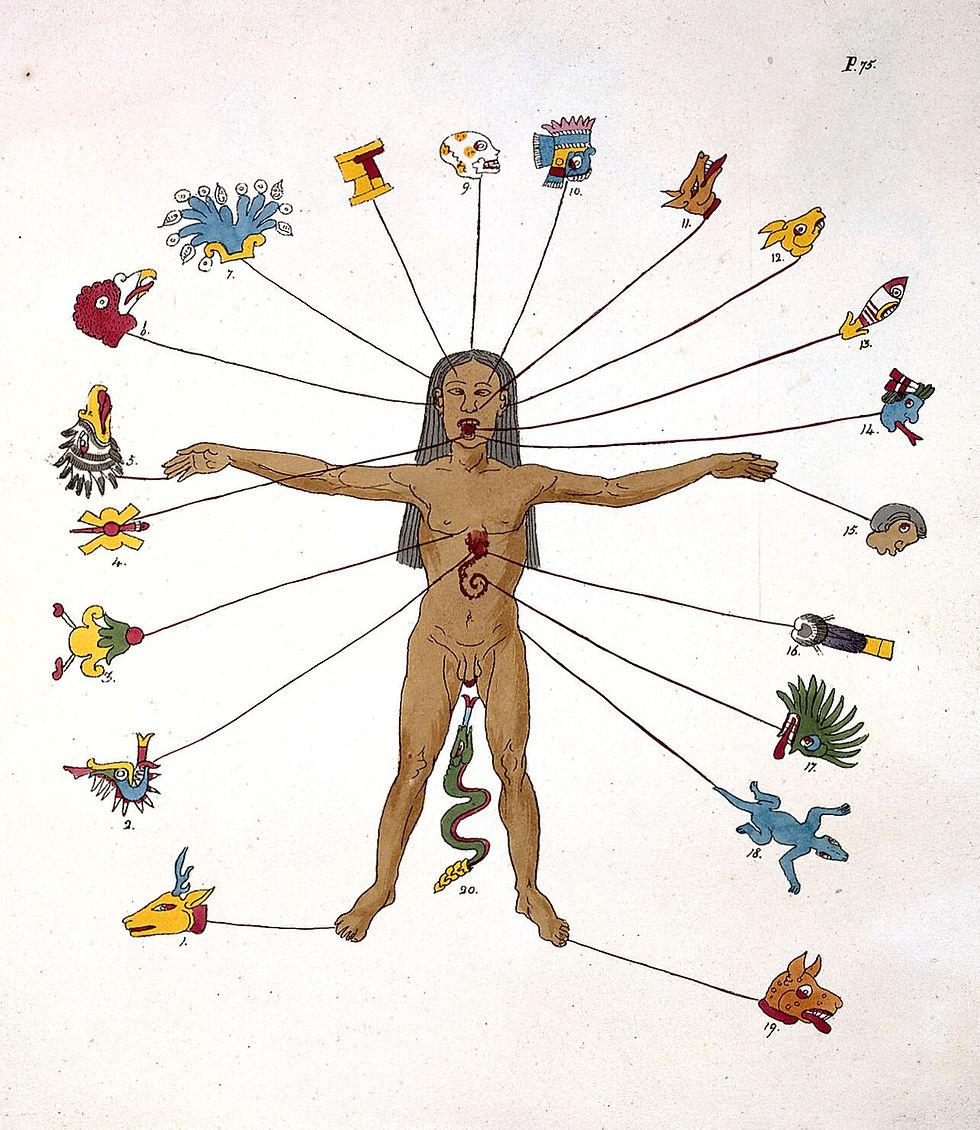

Overall, Bobby exhibited avoidant attachment, and his story serves as a cautionary tale of the risks inherent to avoidant attachment, in extremis.

Having an avoidant attachment meant that under stress and difficult circumstances, Bobby's preferred strategy was to rely solely on himself. He believed that people should be strong and able to handle their own 'emotional stuff'. No mollycoddling.

That strategy was perfectly exemplified in how Bobby dealt with the fallout from the traumatic event. It also dramatically illustrates how, under enough pressure, this approach ultimately fails.

As social beings, humans may have evolved to rely on others as an extended mechanism for coping with stress and hardship. We function optimally by drawing on both internal resources and external support through social connections. The avoidant attachment strategy, however, bypasses this, relying solely on oneself leading inevitable to a heightened and sometimes overwhelming demands on one's own resources.

Would Bobby have developed PTSD and endured its ravages for all those years if he had been 'attached' to others differently? We’ll never know. As his therapist, I can make an informed guess: given how well he responded to therapy, the chances are he wouldn’t have.

Avoidant strategy works until it doesn't. Apply sufficient pressure, and everyone will break down eventually without external help.

On Becoming Avoidantly Attached

Just the other day, I read that having an avoidant attachment often means the person was ignored, criticised, rejected, and utterly neglected.

None of that was true for Bobby though. Bobby grew up in an exceptionally close knit family where mum and dad were loving and caring to their kids and to each other. No major rejection. No utter neglect.

What likely accounts for Bobby’s avoidant attachment is a pervasive family and cultural discourse around bravery and masculinity. There was a general tendency to downplay the importance of emotions, with everyone trying to hide any signs of weakness. Additionally, there was a lack of skill in articulating feelings in a nuanced way that honoured their importance and meaning. In Bobby's words, when it came to feelings, this was the implicit, unspoken rule in his family: "You can tell us anything. But we would rather you didn't".

The family was rich with myths of heroic male figures. For Bobby and his brother, their dad was an invincible hero who never faltered.

This was compounded by the culture of masculinity among friends, where any display of emotion was seen as a legitimate reason for endless ridicule. And naturally, everyone wanted to avoid that. This attitude was both internalised and externalised. Being called a “softy” was the worst possible insult.

Human After All

In an ironic twist of fate, after Bobby opened up to his family about what he was going through—perhaps even after our very first therapy session, if my memory serves—his mum revealed that Bobby's dad had struggled with anxiety and depression for most of his adult life and had been on medication for it, but he never wanted anyone to know. Unknowingly, he had helped perpetuate the cycle of avoidant attachment across generations. As strong as he was, Bobby's dad turned out to be human after all.

Finding the New Self and the Realisation That the Journey Is the Reward: the Post-traumatic Growth

As Bobby began to improve, he sometimes grew frustrated with himself. The recovery seemed never-ending.

While I understood his frustration, as a therapist, I embraced the perspective that we all are imperfections embodied and thus life, especially the examined life, is a perpetual process of change, from small tweaks to major revelations. Ultimately, we are all works in progress.

But that’s OK. There is comfort in realising that the journey is the reward. And I believe Bobby ultimately arrived at that conclusion too.

I think that Bobby is PTSD-free at this point. His condition still might be lurking somewhere from the shadows, so he knows he needs to be mindful of his stress levels and his lifestyle.

Bobby who used to be someone whose main social activities revolved around football and alcohol consumption has decided to stop drinking, realising there is more to life. He is now a dedicated meditator (and puts my own meditation practice to shame). Having chosen to make a major life change, Bobby is now training to become a therapist.

Indeed, we are far from the Bobby that came to see me some years ago. While we could count the years, months, and days according to my therapy records, the changes that have occurred seem unquantifiable by our usual measures of time. A kind of transubstantiation has taken place here, and I like to think that Bobby has found his true self. Talk about post-traumatic growth!

As his therapist, I am incredibly proud of him. It has been an absolute privilege and delight to be a witness to this transformation and recovery.

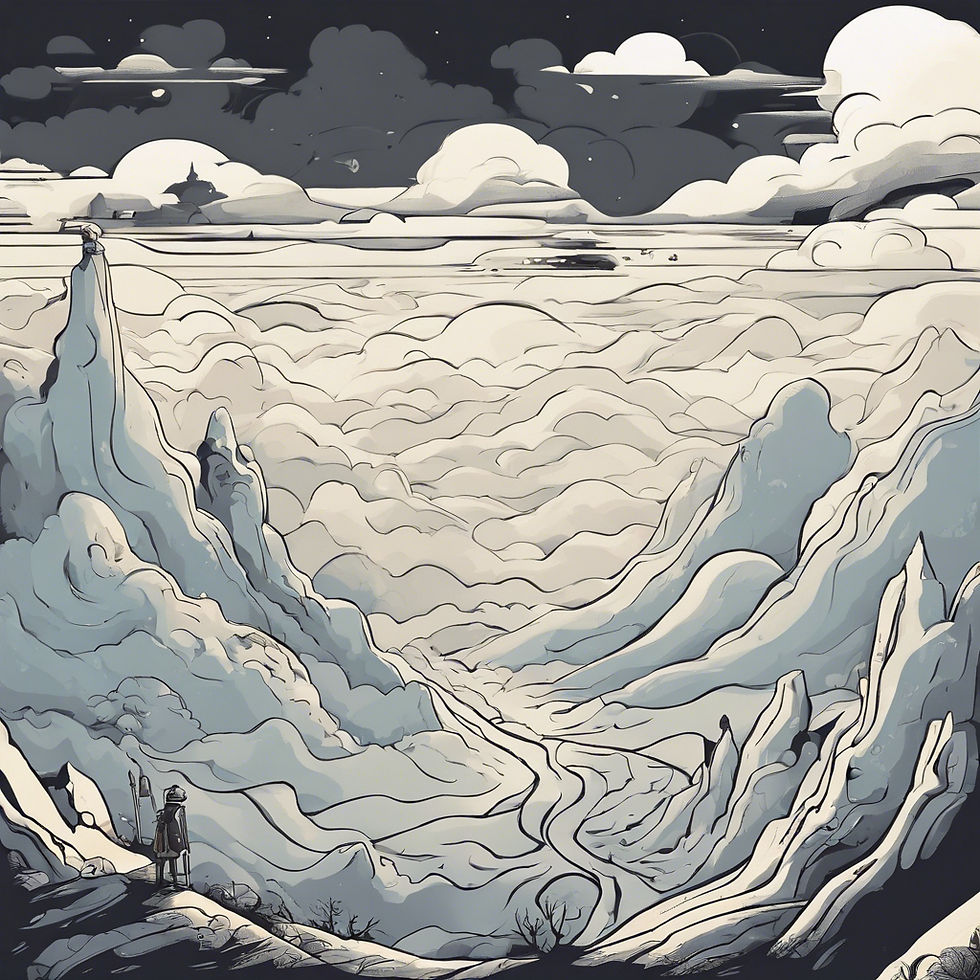

The Dream

Recently, Bobby had a dream, one of those dreams of good omen that feel like they hold a deeper emotional meaning. In this dream, he was standing in a meadow on a hillside, surrounded by bales of straw, green grass, and trees in the distance. The view opened up to the derelict remains of what used to be a cotton mill, a landscape typical of where Bobby and I live. As he observed this vast expanse, he was filled with a deep sense of peace, sensing the protective presence of others just behind him.

In my mind, this dream signified a profound shift in Bobby's outlook on life. While the journey may be one we must undertake alone, others are never too far away to lend a helping hand when we need it.

We have your back. 100%. Go Bobby. Go.

Sometimes we really need to be lost to find our true self.

As always, thank you for reading. For updates you can follow me on BlueSky or Twitter or subscribe to my mailing list.

If you are a therapist interested in the scientific evidence supporting therapy and therapeutic techniques for regulating emotional states, some of the evidence can be found here.

To preserve confidentiality while providing an account of one person's struggle with PTSD, I have changed names and details of events. However, the core facts regarding PTSD symptoms and the journey to recovery remain authentic.

Comments