Our Unreliable Narrator, A Cautionary Tale: N&P Guest Post

- Ana

- Sep 8, 2025

- 7 min read

Updated: Sep 9, 2025

Spotlight on Neuroscience&Psychotherapy readers' publications.

I am so happy to see so many people interested in the neuroscience and psychotherapy nexus. It is the reason for this collection: hearing other people’s thoughts and ideas on this topic I am passionate about.

I had no say over what and how people write their stuff - as long as it fits the criteria, relevant for neuroscience and psychotherapy integration and human-written. I don’t necessarily agree or disagree, approve or disapprove, as this is not about me.

Please read along, give it up for the author and check his substack publications.

Today I feature:

Alex Mendelsohn's piece in which intriguing neuroscience hypotheses abound, but that could also read as a cautionary tale for therapists and clients alike. Alex is a physicist who has spent many hours in psychotherapist’s rooms over the years. You can follow Alex on his substack The Psychiatric Multiverse

I am handing it over to him now.

Our Unreliable Narrator

The left-brain interpreter, therapy, and the cost of missing information

Six months into our sessions together, my person-centred psychotherapist said “I think we are really close to a breakthrough.” I was of the opinion it had already happened. I thought I was thriving.

After developing several severe anxiety conditions1, I returned to my PhD, gave talks at conferences, built a large social network of friends, was part of several sports teams and actively advocated for better mental health practices at the university. As my PhD was coming to a close in the middle of 2019, both my therapist and I thought my condition was improving.

Half a year later I was clinging to life, in immense suffering, as the slow deterioration of my condition reached its nadir.

How did my therapist2 and I get it so wrong?

To partially answer this question, we need to explore the split-brain experiments.

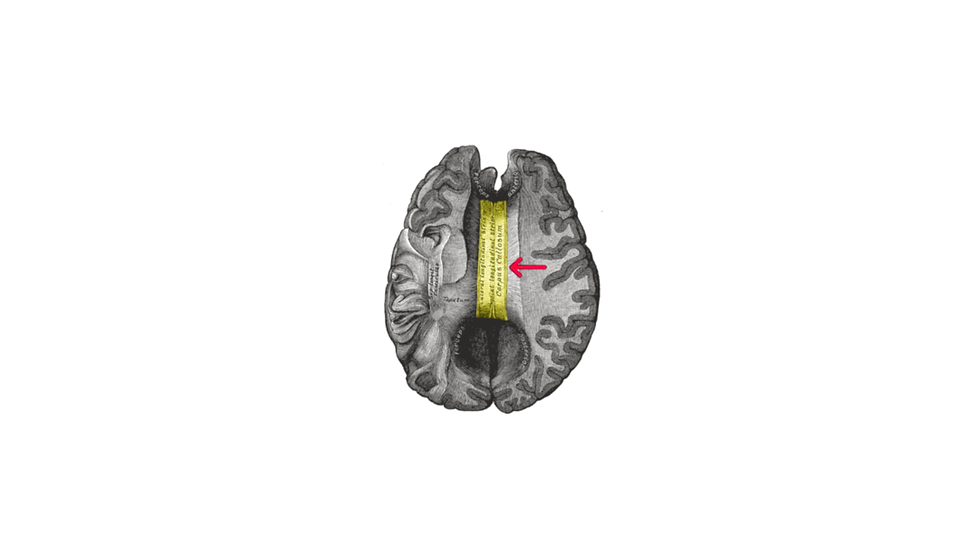

Back in the 1940s, for intractable forms of epilepsy, a surgical procedure was developed to “split” the brain by cutting the corpus callosum, a wide bundle of nerves connecting the two cerebral hemispheres. In addition to the procedure reducing or stopping seizures in most patients, while seemingly retaining normal function, the split-brain patients provided an opportunity to study lateralization of brain processes.

It has been shown that specific functions like language, handedness and facial recognition, among others, are specialised in one of the hemispheres (Though there are many caveats like individual variability as well as myths and oversimplifications associated with left-right hemisphere lateralization – see Ana and Pascal’s previous article andThe Lateralized Brain for a review). The language centre is generally in the left hemisphere, while each hand is generally controlled by the opposing hemisphere.

In a split-brain patient, because their corpus callosum is cut, functions carried out by one side of the brain cannot be communicated to the other. So, information in the right hemisphere cannot reach the language centre in the left. In the 1970s, when the modern era of split-brain research began, neuroscientist Michael Gazzaniga (and his research team) wondered what would happen if information was sneaked into the right hemisphere of split-brain patients.

Using a set up where the split-brain patient would focus on a point on a screen, images can be fed to either side of the brain when placed adjacent to that point (see figure below).

In one experiment using this set up, Gazzaniga showed a split-brain patient’s left hemisphere a chicken claw, and the right hemisphere a snow scene. On the desk in front of the patient was a line of pictures which both hemispheres could see. The research team asked the patient to choose a picture and point to it. The hand controlled by the right hemisphere pointed to the shovel picture (appropriate answer for the snow scene) while the hand controlled by the left hemisphere pointed to the chicken picture (appropriate answer for the chicken claw).

The team then asked why the patient chose those pictures. From an article written by Gazzaniga:

[The patient’s] left-hemisphere speech center replied, “Oh, that’s simple. The chicken claw goes with the chicken,” easily explaining what it knew. It had seen the chicken claw. Then, looking down at his left hand pointing to the shovel, without missing a beat, he said, “And you need a shovel to clean out the chicken shed.” Immediately, the left brain, observing the left hand’s response without the knowledge of why it had picked that item, put it into a context that would explain it.

Gazzaniga called this the “Left-brain interpreter”. If there is information missing that the interpreter does not have access to, it won’t conclude that it doesn’t know; instead, it fills in the gaps with a story that fits the situation. In other words, the left-brain interpreter has no problem confabulating to make sense of the information presented to it.

A follow-up experiment showed that the left-brain interpreter also makes up explanations for mood shifts.

In a similar experimental set-up, the right hemisphere of another split-brain patient was shown a scary fire safety video with a man being pushed into a fire. When asked what they had seen, they replied that they didn’t know, just a “white flash”. But when asked if it made them feel any emotion, they said:

“I don’t really know why, but I’m kind of scared. I feel jumpy, I think maybe I don’t like this room, or maybe it’s you.” She then turned to one of the research assistants and said, “I know I like Dr. Gazzaniga, but right now I’m scared of him for some reason.”

Subsequent experimental evidence supported this initial anecdotal evidence of the left-brain interpreter’s existence3. Further, it has been shown that similar post-hoc rationalisation behaviours can occur in neurotypical people with an intact corpus callosum4. While the right hemisphere plays a prominent role in detecting inconsistencies between hypothesis and reality, when there is information missing – and there is always information missing - your left-brain interpreter will fill in the gaps without you realising5. We are all unreliable narrators, as Gazzaniga concludes:

This is what our brain does all day long. It takes input from other areas of our brain and from the environment and synthesises it into a story. Facts are great but not necessary. The left brain ad-libs the rest.

During my four years in therapy, my head was a persistent, slowly worsening, whirlwind of anxious chaos. But as I had more and more therapy sessions, I felt like my inner world was becoming more coherent. When my anxiety spiked seemingly at random, the explanations I came up with progressively felt more accurate and nuanced. It was all starting to make sense. Until it didn’t.

Psychotherapy did help me build relationships, manage conflict and help me become more emotionally intelligent. I learned many tricks to help manage various minor anxieties. These skills, however, were close to useless when confronted with my growing severe generalised anxiety symptoms. My years in psychotherapy ultimately contributed to delayed psychiatric treatment, with devastating consequences6.

To this day, I still wonder how I could not see the decline. Perhaps I have my left-brain interpreter to partly blame for that.

I was missing information about what a healthy brain felt like. I was missing knowledge about psychotherapy, neuroscience and psychiatry. My psychotherapists were missing information about what it felt like to be in my head, as well as most aspects of my life. Of the information they did receive, it was my personal version of events; they did not have access to other people’s perspectives. If I am brutally honest, my psychotherapists seemed to have extremely limited knowledge about concepts within neuroscience or psychiatry.

Within these information gaps, I would not be surprised if my left-brain interpreter, as well as my therapist’s, ran riot. This begs the question: if, within therapy sessions all over the world, interpreters spring into action during the mood shifts of clients and therapists, what can we do to keep our unreliable narrator in check?

Well, given the right hemisphere of the brain seems to be responsible for checking inconsistencies with hypothesis and reality, this may emphasise the importance of accumulating a diversity of knowledge and understanding. While we cannot fill in every information gap supplied to the interpreter, we can give ourselves the opportunity to challenge and subsequently change the narratives it produces.

For example, I never really got into any discussion about my fears of taking psychiatric medications with my therapist. Because I couldn’t. Neither my therapists nor I knew anything about them. Narratives surrounding psychotropics remained untethered from evidence.

In general, a greater understanding of neuroscience would help bust prevailing myths within psychotherapy. Topics in mathematics like dynamical systems theory could provide us with a different story of how the brain works, or even provide new approaches to aspects of psychotherapy. Exploration of root cause analysis within human factors research, including its issues, might help challenge prevailing theories about finding root causes of mental health problems.

Sticking to what feels safe allows our unreliable narrator to roam free. As someone who has been through the steep learning curve of a PhD, I know how daunting it can feel when first faced by the mountain of new knowledge. But by leaning into the discomfort, appropriate treatment for mental health problems might be found faster. Had I known what I know now, I believe I would have made decisions that would have prevented the worst of my suffering from occurring.

Then again, that could be my left-brain interpreter talking.

Alex’s Bio

Alex Mendelsohn is a physicist and psychiatric patient based in the UK. He has spent many hours in psychotherapist’s rooms over the years, undergoing CBT, psychodynamic and existential therapy, to name a few. He writes on his Substack

It was caused by a serotonin syndrome through a severe reaction to an antidepressant. I’ve written about the experience in a previous article.

and the two previous therapists I went to during my PhD.

See Schacter and Singer (1962) - explanation here, Nisbett and Wilson (1977) - explanationhere, Johannsson et al. (2005) - explanation here & Rebouillat et al. 2021

The situation is a lot more complicated than I am making out. Trying to determine how the lateralization of reasoning works in healthy people is difficult as Turner et al. (2015) explain - pdf available here

I collapsed in exhaustion at the end of the PhD and had to move back home with my mum, who then cared for me after a dramatic decline in functioning. It took a further two years to find a medication that started to slowly reduce the generalized anxiety symptoms. The psychiatric system is not the most efficient.

While I have made substantial progress since, currently, a decade after the serotonin syndrome which precipitated my mental illness, I am still unable to work, and still trying to rebuild my life. In cases like mine, early intervention is key.

Comments