As Above, So Below: the Role of the Thalamus in Politics of Experience

- Michael H & Ana

- Jul 24, 2025

- 13 min read

Updated: Jul 26, 2025

Who is in charge when it comes to deciding what you see, hear, notice, think and feel? Who decides of the politics of experience?

Co-written Michael Halassa and Ana

Politics of Experience

Do you ever ask yourself why something enters your perception at a given moment? After all, there are a million and one thing that could draw your attention at any time. So why that specific one?

And do you ever wonder the same thing about your thoughts? Why does a particular thought coalesce in your mind at a particular moment? At any given time, you could be thinking a million and one different thoughts, related or unrelated to the myriad things surrounding you. Yet it happens to be just that one.

To be sure, it is partly going to be down to your personal history of experiences. The things that you notice, the things that ‘stick’ and go on to act as a ‘seeds’ for thoughts are, to a large degree, a function of the history of you.

One simple example is the Baader-Meinhof phenomenon (aka the frequency illusion) where we essentially start seeing something that is salient for us everywhere (new baby, new car etc). Salient, by the way, is just a fancy way of saying that something is relevant and deemed of importance and interest for us at a given moment.

But actually, the same principle applies to virtually everything that we end up perceiving. For example, if you are an anxious person, or someone with social anxiety, your thoughts might spontaneously gravitate towards certain kinds of ‘attractor’ states. Noticing potential threats, reasons to be worried or how judgemental or unfriendly others might seem will all be high on the list. If you are depressed, it will be drawn towards different kinds of things altogether. If you think about it, they are all different politics of experience.

So who chooses what we are to notice and end up thinking about? Is there a meaning to that process? Furthermore, what kind of brain mechanics is behind it? In other words, who or what is in charge of the politics of your experience?

To try to answer, we first need to define thinking.

Thinking About Thinking

We think all of the time. We are so used to thinking that, most of the time, we are not even aware of it. Sometimes thinking can even get out of hand. We are overthinking it.

And here, thinking doesn’t necessarily mean thinking as in rational thinking. More like what encompasses all the things that go through our mind, what reaches our conscious awareness.

But what is thinking really? That is not so easy to define. And furthermore, what are its neural correlates? In other words, what happens in the brain for thoughts to arise?

Thoughts might feel as ‘clouds in the mind’ that have a meaning. Sometimes they present as an intelligible voice that converses with us. At other times, they are more elusive. Just a flutter. Sometimes thoughts can be rather shouty. Even intrusive voices. Thoughts can be ‘sticky’, lingering in the mind or they can be fleeting.

To try to define thoughts phenomenologically even further, it feels as though a thought should have some content and some feelings or attitudes towards that content. There certainly are several types of thoughts: inner speech, inner seeing, feelings or emotions, sensory awareness and unsymbolised thinking (explicit thoughts that don’t include the experience of words, images or symbols). And then of course, a chain of any possible combinations of those.

Here is an iconic example of a chain of thoughts triggered by a sensation (reminiscent of Marcel Proust’s famous scene in In Search of Lost Time):

Do you know what a petite madeleine is? It’s a very small and very French soft biscuit, shaped as though it had been moulded in the fluted scallop of a pilgrim's shell. It’s made with lots of butter, a little flour, and eggs, and it has an unmistakable almost almondy aroma to it.

Now, if you’re French, and if this is something you used to eat freshly baked as a child, the sight and smell of a madeleine is likely to trigger, at first, a pleasant sensation and then some memories of childhood. But perhaps your thoughts might then ‘jump’ to an old childhood friend. Then a time that friend let you down might come to mind and with that, you might recall the feeling of hurt. That memory might stir a pang of sadness and transport you back to the present, to a recent moment when someone you trusted let you down in a similar way. A disheartening thought might then arise: do things ever really change in life?

And before you know it, the simple smell of baking propels you into a deep reflection on the nature of life. How did that happen?

While thoughts often seem to arise spontaneously, they are ultimately created in the mind and some sort of physical selection must be taking place regarding what their specific content will be for each individual at a given moment. After all, one person’s thoughts are likely to differ from another’s, even if all external circumstances are the same.

The crucial question for us here is this: how and where in the brain is the unfolding and selection of our thoughts determined?

How Thoughts Work (Maybe)

Everybody knows this: thinking is the province of the prefrontal cortex. Right? The prefrontal cortex is disproportionately developed in humans, making thinking a prized human attribute.

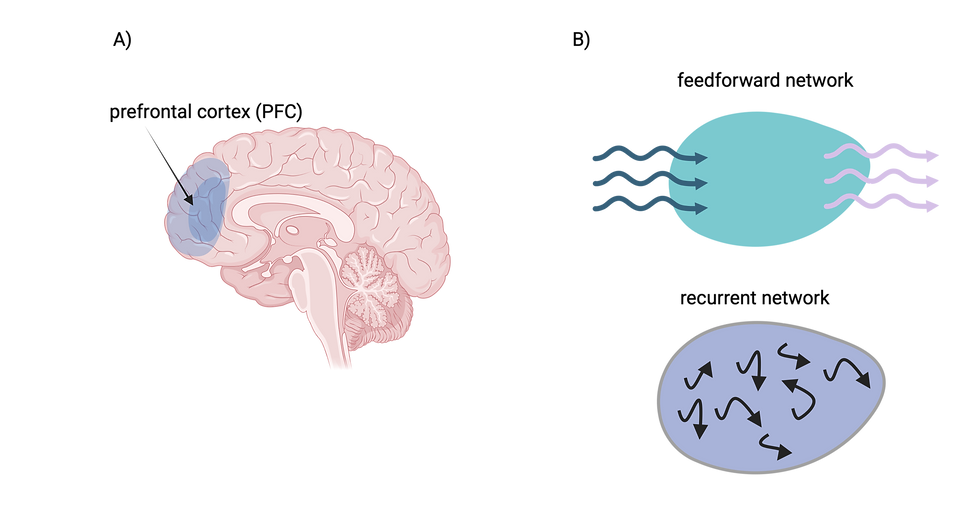

If we want to get a bit more technical, at a very high level, thoughts are probably related to brain circuitry that can generate activity in the absence of any input. This kind of brain networks are referred to as recurrent. In contrast to these recurrent networks, some brain networks are feedforward. Feedforward means that the network is input driven and their activity is tightly linked to whatever is fed to them at that time. In feedforward networks, when the input is off, there is no one home.

The brain is composed of both feedforward and recurrent networks.

Subcortical structures such as the thalamus and the basal ganglia are feedforward - meaning they process a certain input into an output. While on the other hand, the cortex, including the prefrontal cortex, is recurrent and can therefore display persistent activity in the absence of an input (we think by default, even if nothing is happening).

One model of how thinking could work is that the more cognitive aspects of thinking are generated within the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and to get more details into thought, the PFC has to ‘ping’ (higher and lower order) sensory areas to fill in the details.

Also, the PFC contains networks that are able to maintain activity patterns over the longest timescales across all of the cortex. This would explain why we can keep and keep on thinking.

Now that we have sort of an idea about what thoughts might be, and where they happen, we can return to our initial question: who or what chooses what we think?

As Above So Below: the Role of the Thalamus In Thought Selection

Can you see where this is all going? It was all a long-winded way to get you to the point where you can see how the narrative of thinking being an essentially prefrontal cortex affair has been recently overturned.

As it turns out, some important aspects of thinking happen in a deep subcortical structure called the thalamus, located near the centre of the brain.

While the process of thinking itself takes place in the prefrontal cortex, what we think about may be just as crucial to the process as how we think. And, as it happens, the thalamus, this deep subcortical structure, plays a key role in determining the content of our thoughts. As above, so below.

One thing that is special about the thalamus is that it has connections to almost every other structure in the brain. But many of these connections are ‘topographic’ or orderly. Meaning, there are parts of the thalamus that are connected to the visual cortex, others connected to auditory and so on. These parts had been extensively studied in the early history of neuroscience and therefore, the thalamus became known as “the sensory hub of the brain” in standard neuroscience textbooks.

The textbooks describe the thalamus as a ‘relay’, because it is made up of neurons that do not ‘talk to each other’ and appear to simply pass on messages to the cortex. As such, the part of the thalamus in charge of passing on the visual information would just relay the visual information to the cortex, without having any say in what goes in and what is left out.

But, it turns out, that this classic idea of the thalamus as a sensory relay is in fact not entirely accurate. Neuroscience has come to understand the role of the thalamus more as one of a ‘smart filter’ rather than a ‘relay’. This point is key to our story. And if there is a filter, there must also be criteria the filter uses to decide what information to keep and what to discard.

The criteria for the thalamus to act as a filter of sensory experiences is what the brain ‘cares’ about in that specific moment. And, as we shall see later, it is thought that it is down to what the brain predicts to be the most essential information out there in order to keep us well and alive, given our prior experience. We can also call that attention. Attention has a strong influence on what the thalamus passes to the cortex and what it filters out.

But perhaps the biggest surprise about the thalamus has emerged in the last ten years or so: its involvement in the filtering of thoughts.

Remember, neurons in the thalamus do not talk to each other. We called that feedforward network from the previous section. In the cortex, however, they do (recurrent networks). As we have mentioned, that feature allows the cortex to hold on to ideas for a long time. The neurons in the cortex also mix many signals together, because it allows them to do all kinds of interesting computations. It also allows for making all sorts of connections about things in the outside world that are not obvious from the incoming data.

In our earlier example, our French person would be able to encounter a madeleine they have never tasted before, and quickly be able to discern the ingredients that have gone into it based on mixing various prior combinations in hypothetical madeleines and matching them to this new experience.

But the powerful computational machinery in the prefrontal cortex comes at a cost: there is too much going on. Once you have so many things mixed, it becomes hard to figure out what’s what.

One imperfect metaphor for the prefrontal cortex that we could employ here is that of a conductor of an orchestra. It sends ‘instructions’ to the rest of the brain to organize sensation (input), enact behaviours (output) and retrieve and store memories (input and output). These links are the fundamental building blocks of thought, which are sent back to the prefrontal cortex to enter conscious awareness.

But because of so much going on in the PFC, it becomes hard for the rest of the brain to :

Decode what the instructions of thoughts are: because the internal machinery of the PFC mixes information, sensory or motor regions decoding what the PFC is instructing their own content or communication with one another becomes difficult.

Assign ‘credit’ to events – meaning that when the the ingredients of thought are all ‘mixed-up’ and an error occurs in how the brain responds to a certain situation, it is hard to know what caused this bad outcome.

If we use the mixing metaphor from before, then all boils down to the question of how is the content from the PFC ‘de-mixed’?

Thalamus As A Thought Filter

That’s where the thalamus comes in handy. Some parts of the thalamus are nonsensory - meaning that they are not filtering the sensory incoming information only. One of them, called the mediodorsal thalamus (MD), ‘plugs in’, so to, speak to the prefrontal cortex. As a PFC ‘plug-in’, it operates as a filter of the ‘instructions’ from the prefrontal cortex, and the ingredients of thoughts.

Let’s illustrate this with an example (which also gives a sense of how wrong inferences can easily be made):

Say you are getting on the train and as you are finding your seat, some people start laughing. That draws your attention - how others see us, even if only strangers, matters to us - and the brain starts generating hypotheses - out of awareness - what might be the matter here. Why are they laughing? It is then that the mediodorsal thalamus narrows the decision of ‘what to think’, weighing probabilities that depend on parameters that include our catalogue of similar experiences and our past history of relationships with others. So in this specific case, we might ‘decide’ that the people laughing in the train was down to a joke they were telling and unrelated to you or your outfit, and you don’t end up feeling self-conscious or embarrassed.

Now, for simplicity, let’s call this thalamus ‘plug-in’ a thought filter. As we have seen, in the prefrontal cortex, information is mixed and it is difficult to know what's what. The mediodorsal thalamus is effectively ‘de-mixing’ this information. Here is how we might think about this process using a real life example:

Imagine a scenario where you meet a new person you have never met before. And let’s say that you want this person to like you, for whichever reason. So this person is, at that specific moment, important to you.

And now you’re trying to figure out what is the best way to be with this person, as you want them to like you. So maybe even out of awareness, you are trying to bring up the ‘rules’ of the best way to be, or the best ‘game to play’ with that specific kind of person (as in psychological games).

To do so, the brain likely retrieves a memory (out of another part of the cortex or out of another subcortical area - the hippocampus) and ‘uploads’ it in the prefrontal cortex. Because the prefrontal cortex is such a powerful machine, different rules for ‘game playing’ can be uploaded into it. But to figure out where this specific new person fits, the brain has to have a mechanism to separate these rules.

And that mechanism is likely the neurons of the mediodorsal thalamus. These neurons can effectively separate between different ‘games’ and their ‘rules’. Because, as we have seen, the neurons in the thalamus do not talk to each other, this minimizes interference and the search process can be seamless. This is effectively thought filtering.

Now, going back to our example of that encounter with a new person, how do we actually decide on our course of action?

By having specialized machinery for de-mixing sources of information, the mediodorsal thalamus also has the capacity to represent their ‘reliability’ and aid the prefrontal cortex in making decisions that are 'optimal'.

And to be sure: invoking the idea of ‘optimal’ might sound like we are just kicking the can down the road without really answering the question. However, going down that rabbit hole would probably take us to the point where even your thalamus would not be able to de-mix all the information from this paper. So let’s just say, for now, that it is believed today that the whole process is in line with the ideas of the brain as an active inference device, positing that, instead of being a passive receiver of information that reacts, the brain perpetually tries to pre-empt our needs through making predictions. In that way it is possible to prepare us to what is to come based on the best ‘guess’ that it can make at that given moment based on the current conditions (from exteroceptive and interoceptive signals) and, crucially, prior experiences.

While the results so far refer mainly to the executive circuits (thinking) it is possible that the emotional thought selection/filtering in the medial prefrontal cortex may involve the thalamus through analogous mechanisms.

OK. So What?

You might be a psychotherapist who is a bit of a neuroscience nerd or simply someone who finds beauty in understanding how things work. After all, thoughts are quite an unfathomable phenomenon: pervasive and ever present yet abstract and seemingly completely immaterial, making thinking about mechanics of thought and its physical underpinnings mysterious and mind boggling. Thoughts are forever fascinating. Gaining some understanding of how they are formed, at a fundamental level, has surely got to be interesting. Even for therapists.

But can we push the envelope a little further? Could we - and should we - explore whether some of these advances in understanding of mechanisms of thought can help us in therapy? Remember, here we use a broad definitions of thoughts that involve feelings, images etc.

Although there is no certainty at this point, here are some elements that weigh in favour of that possibility. Think of the following:

General Anxiety Disorder

Social anxiety

Body dysmorphic disorder

PTSD

Depression

Experiencing hallucinations and psychotic disorders

Attachment presentations

Now, these presentations are all very different - from the point of view of experience, psychology, physiology, symptoms, worldview, and more. They don’t even share the same blind spots.

But...one thing they all do have in common is that they have a blind spot.

In other words, each one comes with its own distinct set of blind spots or biases . Let’s look at a few and you can fill in the rest. In anxiety, it’s a bias towards perceiving threat: how dangerous things are, how much we need to worry. In social anxiety, it is about how frightening or judgmental others are. In PTSD, it’s ultimately about how safe we are in the present moment. In the case of hallucinations, perception itself is biased. Now, this is not to say that these presentations are reduced to only the bias and nothing but, right? But they are part of the story.

And when we talk about a blind spots or biases, what we are really saying is that there is a problem in how we select the relevant information, right? And that brings us back to the thalamus.

To be sure, all the connections we make here are very tentative and can form only vague conjenctures. Nothing tells us exactly how the thalamus would mediate information in each one of the specific examples of presentations listed above. And the leap would be even bigger when it comes to any potential translation into therapy practice. As cool as these ideas might be, at this point, they are only that: cool ideas. But cool ideas give us food for thought and can hopefully lead to cool discoveries.

In addition, you now know that, when it comes to where thinking happens, as the old saying goes: It is as above, so below.

As always, thank you for reading 🙏.

Guest Bio

Michael Halassa is a professor of neuroscience and psychiatry at Tufts University in Boston. His lab investigates the neural mechanisms underlying executive function and his clinical practice focuses on psychotic disorders. You can follow Michael and find out more about his work on his substack.

Deeper Dive: Recommended Reading

Thalamocortical architectures for flexible cognition and efficient learning A review that directly addresses the mixing, de-mixing.

The impact of the human thalamus on brain-wide information processing | Nature Reviews Neuroscience This is a highly cited review in humans.

Thalamic control of functional cortical connectivity - ScienceDirect A less technical review.

Any thoughts on how this may be linking to what we know about the neuroscience of mindfulness?

~Jehan